EDUCATIONAL AND CLINICAL PRACTICE ORIGINAL RESEARCH • Bedside Abdominal Ultrasound in Evaluating Nasogastric Tube Placement

Source: CHEST 2021; 159(6):2366-2372

INTRODUCTION

Nasogastric tube (NGT) is commonly used in daily clinical practice for a variety of indications such as administration of enteral nutrition and medications, gastric decompression, irrigation, and diagnostic procedures. Correct placement of the NGT is initially confirmed by auscultating air administered through the tube (whoosh test); this is often considered adequate confirmation even without obtaining a chest radiograph, which is the considered the diagnostic “gold standard” for correct NGT visualization.

Yet, chest radiograph has several disadvantages such as a source of irradiation, time-consuming, and it may not always be definitive. Therefore, the authors decided to evaluate the feasibility of bedside abdominal ultrasound (BAU) to confirm correct NGT placement in a large, prospective, multicenter cohort study.

METHODS

This was a prospective multicenter study (eight centers) of consecutive adult patients (> 18 years of age) who had an NGT placed during their hospitalization throughout a 36-month period. Exclusion criteria consisted of pregnancy, age < 18 years, tracheostomy, refusal to provide written informed consent, anatomic deformity, and contraindication for NGT placement: caustic substance ingestion, neck surgery, and nasal or cranial fracture.

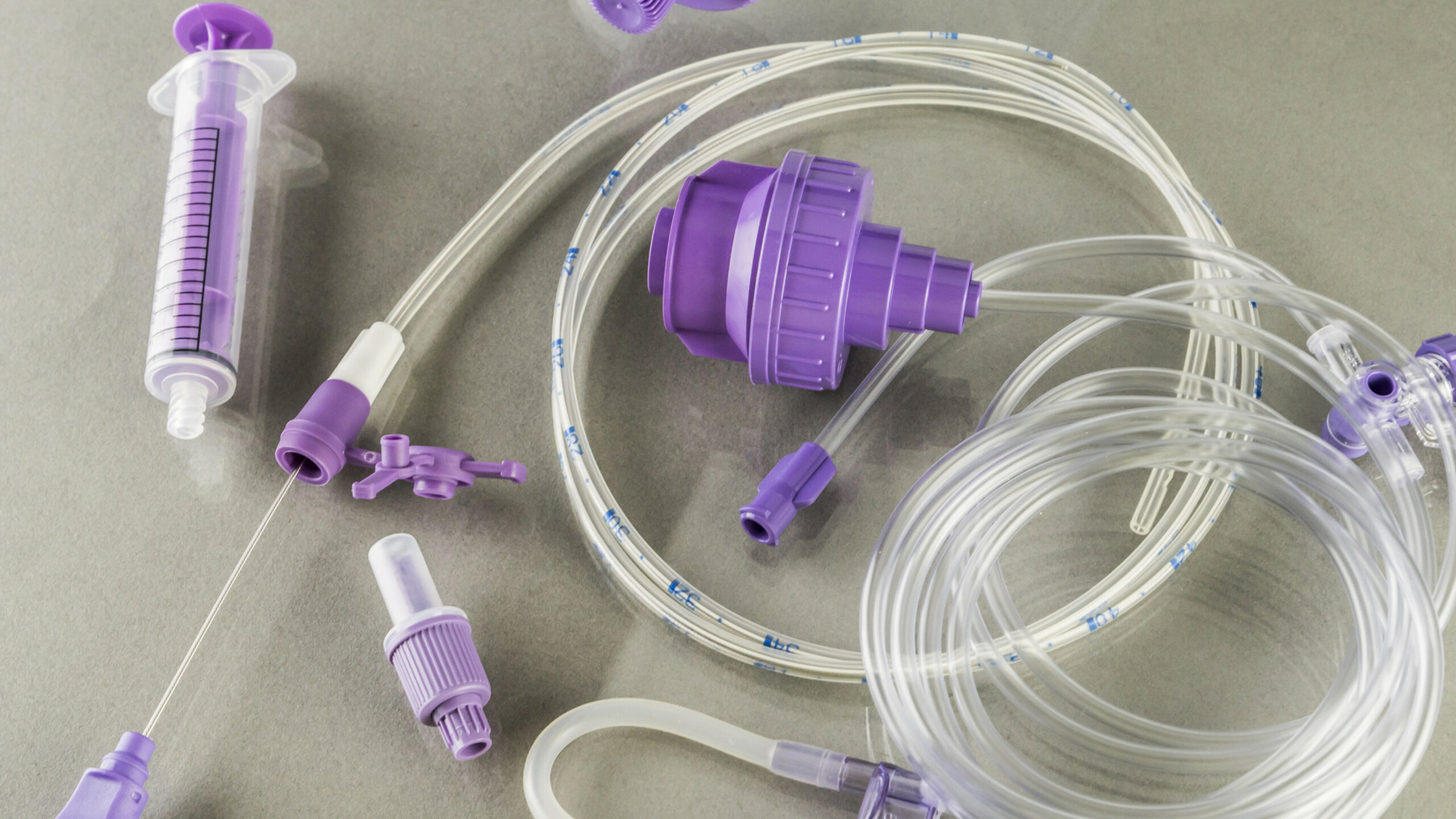

10F-16F caliber NGTs and real-time portable ultrasound units equipped with a convex probe with low frequency (2-5 MHz) were used in the study. All the NGTs were positioned by nursing staff not involved in the ultrasound study. After positioning, the same operator checked for correct placement, listening for the sound provoked by air insufflated in the NGT (whoosh test). Gastric placement of the NGT was considered correct if the sound was heard over the epigastrium.

The BAU was performed by expert in ultrasound with a specific 10-h training course (physicians or nurses) who were not involved in the NGT placement. They considered two possible criteria to confirm correct NGT location in the stomach:

- The NGT directly identified as a single or double hyperechoic line

- When visualization of the NGT was not achieved, 40 mL of air was injected through the gastric tube and gastric placement of the tube was confirmed if ultrasonography showed dynamic fogging in the stomach

The ultrasound operators were blinded to each other and completed a prespecified study form with patient characteristics and the results of all the diagnostic tests immediately after the examination. There were three possible answers: correct, incorrect, or uncertain placement of the NGT in the stomach.

A chest radiograph was obtained from all of patients either during or at the end of the procedure and the reporting radiologists contemplated only two answers: correct or incorrect placement.

RESULTS

Five nurses and 15 physicians with ultrasound experience in the cardiovascular field had a specific, 10-h course in bedside abdominal ultrasound. They scanned 526 patients in 8 centers. The mean age was 77.4 + 11.9 years, and 58.4% of patients were male.

In 438 patients (83%) chest radiography confirmed correct NGT placement in the stomach; in 326 patients (75%) and 408 patients (93%), NGT placement was correctly identified by whoosh test and by BAU, respectively. The k statistics agreement between chest radiography and ultrasonography was excellent with a weighted Cohen k of 0.94. The time gap between ultrasound and chest radiography was a maximum of 30 min for all the included patients.

BAU was positive, negative, and inconclusive (i.e., the NGT was not seen, and we were able to see only a little fog of air contrast) in 415 (78.9%), 71 (13.5%), and 40 (7.6%) patients, respectively. Excluding inconclusive results, BAU had a sensitivity of 99.8%, a specificity of 91.0%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 98.3%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98.6%.

CONCLUSIONS

The authors concluded that BAU had good positive predictive value and accurately confirmed correct placement of NGTs when compared with chest radiography, but the number of false positive results is not negligible.

The authors commented that the rate of inconclusive results was quite high, and therefore they believe that caution is necessary before implementing this technique in clinical practice because of the potential consequences of using a misplaced nasogastric tube.

English

English

Español

Español