ED Point-of-Care Ultrasonography Is Associated with Earlier Drainage of Pericardial Effusion: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Source: AJEM 60 (2022) 156–163

INTRODUCTION

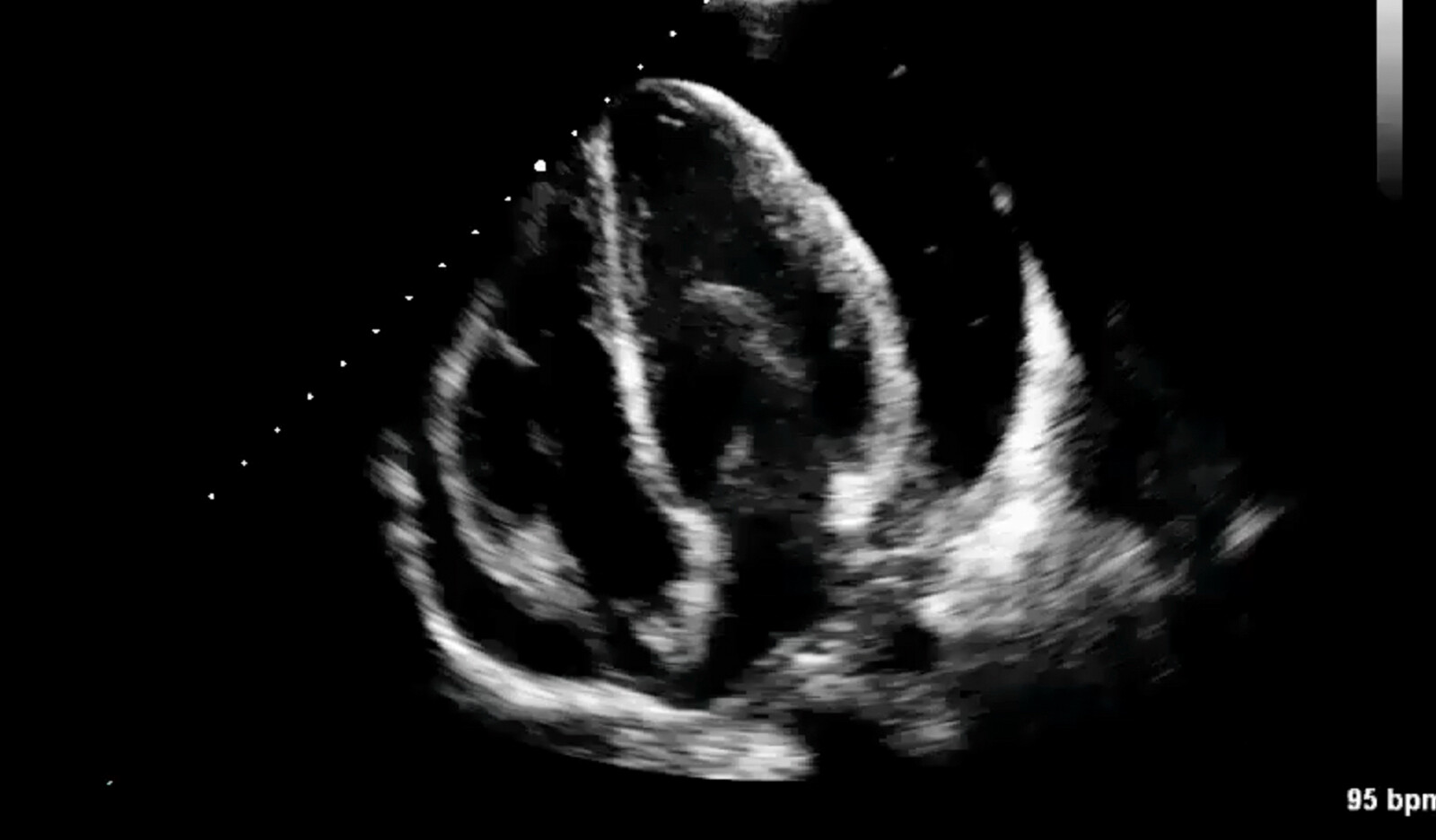

Pericardial effusions represent a clinical spectrum of disease ranging from asymptomatic to obstructive shock and can be the etiology of nonspecific cardiopulmonary symptoms, unrecognized shock, and abrupt clinical deterioration. Therefore, identification of pericardial effusion remains challenging in the ED, especially in patients without overt signs of shock.

Point-of-care-ultrasonography (POCUS) for the identification of pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade is a core skill in emergency medicine. Emergency physicians have been shown to reliably identify pericardial effusions and echocardiographic signs of cardiac tamponade with POCUS, leading to more rapid identification of cardiac etiologies for dyspnea and shock.

The primary goal of this study was to evaluate the impact of POCUS on timing of intervention for pericardial effusions in patients who had a procedure to drain the effusion.

The authors also evaluated trends in POCUS utilization during a period when the emergency ultrasound program was established at their institution. The authors hypothesized that patients who underwent POCUS performed by the emergency physician would have earlier intervention for pericardial effusion.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study utilizing electronic health record (EHR) data to evaluate the effect of ED physician performed POCUS on time from presentation to intervention in patients with a pericardial effusion.

Intervention was defined as the performance of a pericardiocentesis, placement of pericardial drain, pericardial window or other surgical procedure to remove fluid from within the pericardial sac. The study timeframe spanned eight years (July 1st, 2012, to June 30th, 2020) and during this time, major changes to the POCUS workflow and education occurred in the ED.

Setting, participants, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

The study was performed at an urban academic tertiary care medical center with a high volume of oncology, cardiac surgery, and other specialty care. Patient encounters originating in the ED during the study timeframe were reviewed and those with ICD-9, ICD-10, and CPT-4 billing codes for pericardiocentesis and related procedures were included in the cohort. The cohort was limited to pericardial effusions that required drainage on the same encounter as these were considered clinically significant.

Exclusion criteria included pericardial interventions performed due to traumatic pericardial effusion or aortic dissection, as well as encounters where a pericardial effusion was the direct complication of another procedure occurring after admission from the ED.

Ultrasound program and changes

Prior to fiscal year 2015, the authors’ department had access to ultrasound equipment and residency curriculum for bedside ultrasound, but limited infrastructure (early period). They then hired focused practice designation (FPD) eligible advanced ultrasound faculty to establish a quality assurance program with focused educational feedback and to redesign POCUS curricula at the start of fiscal year 2015 (transition period beginning 7/1/2014). They established an orders-based workflow including ordering of all POCUS studies in the EHR, electronic image archiving and mandated imaging study documentation at the beginning of fiscal year 2018 (late period beginning 8/21/2017).

Variables

The primary exposure of interest was cardiac POCUS performed by the ED physician. This was defined as any reference to the performance of POCUS by the ED physician including an interpretation of the images found by reviewers in the ED, inpatient physician documentation, consultant documentation, or a separately documented report of imaging findings.

The primary outcome was time to intervention which was defined as the time of ED presentation to the skin incision time if the procedure was performed in the operating room or the first vital sign timestamp if the procedure was performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. If the procedure was performed in the ED, the physician and nursing documentation was used to ascertain the exact time of the procedure.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and data collection reliability

Three hundred forty-five patient encounters meeting the inclusion criteria were identified using the initial search strategy based on ICD and CPT codes. After exclusions, 257 total encounters were identified as eligible with 137 who received POCUS and 120 who did not over the eight-year study time-period.

No significant differences in age, gender, race, comorbidities, time of presentation or anticoagulation were observed between groups.

Characteristics of ED evaluation and pericardial effusions

Patients who received POCUS more frequently had chest pain or shortness of breath as their chief complaint, but this difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, POCUS patients were also more likely to have pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade diagnosed in the ED. In addition, POCUS patients were also less likely to have a cardiology-based echocardiogram prior to intervention.

Time to intervention for pericardial effusion

In univariate time to event analysis, median time to pericardial intervention (first pericardiocentesis, pericardial window or other surgical procedure) was 21.6 hours in the POCUS group and 34.6 hours in the No POCUS group.

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the adjusted median time to intervention. POCUS was associated with earlier intervention (HR 2.08 [95% CI 1.56–2.77]) after adjustment for age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index, anticoagulation, night or weekend rooming in the ED, and hemodynamic instability.

Night or weekend rooming was associated with delayed intervention (HR 0.67 [0.51–0.88]). Point estimates for initial hemodynamic instability suggested earlier intervention if patients were initially unstable but this effect was not statistically significant (HR 1.37 [95% CI 0.96–1.95] for MAP <65 mmHg and HR 1.32 [95% CI 0.96–1.81] for Shock Index ≥ 0.8).

When time to intervention was stratified by the US program period, there was no significant difference in median time to intervention across time periods for the POCUS group and for the No POCUS group. Within each time-period, median time to intervention was earlier in the POCUS group.

CONCLUSION

The author concluded that in this single-center retrospective study of patients who underwent pericardial drainage, POCUS was associated with an earlier time to intervention after adjustment for multiple confounding factors.

In addition, POCUS was not associated with a difference in 28-day mortality or a significant reduction in hospital and ICU length of stay. However, they also noted that failure to diagnose pericardial effusion using any diagnostic testing including POCUS, was associated with significant increases in both 28-day mortality and length of stay

Español

Español

English

English